The Youngest Believers

Around this time of year, thoughts turn to family. Time spent together, yes. But, for parents who've split up, time spent apart--especially from the children. Anyone who has gone through a divorce knows the pain of a custody agreement. Who would think that the Shakers had their own custodial contracts regarding the sons and daughters of believers? And who would think that those documents could be more unyielding than the toughest divorce papers?

Shaker children's chairs

When a family presented itself to a Shaker community, its members pledged many things. They gave up their land and personal property. They agreed to confess to all of their sins. They promised to forgo all relations with the opposite sex--especially those of a "carnal" nature. And they pledged to break all blood ties. Husbands and wives, parents and children, sisters and brothers--none of those relationships were allowed by the Shakers.

Often, poor families or families that had lost one parent to death, conscription, or simple abandonment were forced to leave their children with the Shakers while they attempted to better their circumstances. The children, after all, would be well looked after by the sect. There were food, medicine and schooling to be had; there would be a roof over their heads; they would be kept warm and well-clothed; and they would receive a good education, both academically and in various trades and domestic areas. They were likely, in almost every way, to be better off than when they lived with their real families.

Two Shaker boys drawing water from a well

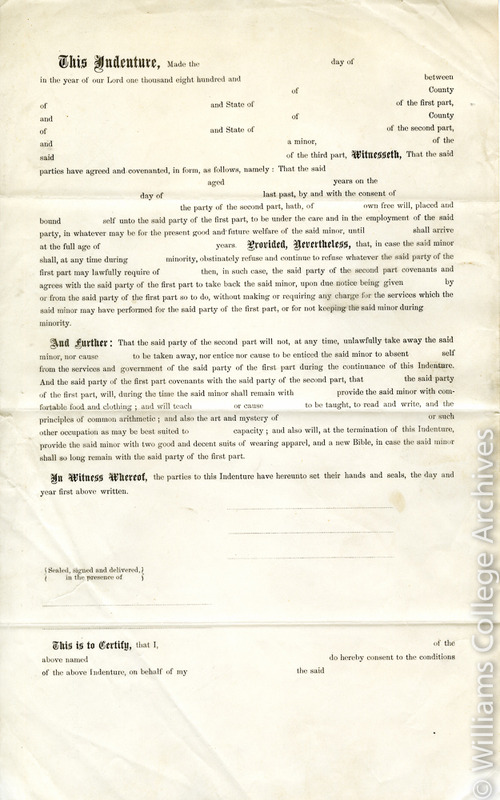

The catch? They couldn't go home. Parents who decided they could not stay with their children--whatever the reason--had to sign contracts of indenture, essentially handing over their sons and daughters to the Shakers until the children reached the age of twenty-one, at which point they were allowed to decide on their own whether to remain with the Shakers or "go into the World."

A Shaker contract of indenture

Often, parents would attempt to steal back their children. Sometimes, children attempted to run away or, as the Shakers put it, to "elope." There are records proving that Shaker communities occasionally transferred to another settlement a child at risk of being stolen or turning into a fugitive. But many children preferred their orderly new lives to the impoverishment, abuse and/or neglect they had experienced in the past. Needless to say, the Shakers didn't insist on keeping every child: obstinate troublemakers--those beyond all redemption--were returned to their parents for fear that they might infect their peers with their "Worldly attitudes."

Mary Marshall Dyer

The Dyer clan suffered more than dissolution because of the Shakers' rules of indenture. In 1813, Joseph Dyer, his wife Mary, and their children, Caleb, Betsey, Jerrub, Joseph Jr., and Orville, joined the settlement at Enfield, New Hampshire. Two years later, Mary Dyer left the community claiming that, by keeping its members apart, the Shakers had destroyed her family. She began a campaign to get her children back, attacking the Shakers in writing and in the courts. She became an activist, assisting others with the same battles, but she never won her own case. Her husband and all but one child remained devout Shakers. Indeed, Mary’s oldest son, Caleb, became the head trustee of the Enfield settlement.

A group of Shaker girls

The Dyer family's trouble with indenture did not end with Mary's struggle to reclaim her children. In 1861, a local shoemaker named Thomas Weir enlisted in the Fifth New Hampshire Volunteers. His wife was recently deceased so, before leaving to fight in the Civil War, Weir indentured his two youngest daughters with the Enfield Shakers. In May of 1862, he was discharged with a disability, returned to Enfield, and demanded to have his daughters back. After repeated attempts to regain his children, he turned up at the settlement brandishing a gun. Elder Caleb Dyer--now a grown man but himself the subject of his mother's court battles over indenture--refused once again to let Weir have his daughters. Weir shot Dyer in the abdomen and he died within 48 hours.

Weir never got to see his daughters grow up. He was arrested, convicted of murder, and sentenced to prison for 30 years. He served 13 and lived out the rest of his life in Enfield, occasionally doing odd jobs for the Shakers.

One last note: The Shakers used the word "family" all the time. For them, it described small communities--the Church family, the North family, the South family--within the larger settlement. The way they saw it, men and boys were brothers, women and girls were sisters, and everyone was a child of Mother Ann Lee and…Jesus Christ.